|

|

Egypt Exercise 7.1 - Amarna & Egyptian TemplesPart 1: The City of AmarnaAkhetaton, capital of Pharaoh Akhenaton (c. 1350-1334 BC)The city of Akhetaton, called Amarna today, gives us a remarkable insight into ancient Egyptian town planning. This urban center of around 50,000 (a large number by ancient standards) was built quickly on virgin desert when Akhenaton decided to move the capital and religious center of Egypt from its traditional location at Thebes to a new place where he could realize his radical monotheistic religious "revolution" to the worship of the sun god in the form of the Aton, represented as the sun disk with rays of light shining down, bringing life and propserity to the people of Egypt and the world through his main representative on earth, Akhenaton (literally "Servant of the Aton"). Akhetaton means "Horizon of the Aton," reflecting Start by hitting the link "Amarna the Place" and move on to the "Model of the City." Once you have reviewed these web pages, feel free to explore the other materials on this site. Part 2: "Temple as Cosmos"Medinet Habu, the mortuary temple of Ramses III (c. 1182-1151 BC)Akhenaton's monotheistic vision of the Aton led to a complete emphasis on temples characterized by large open spaces. Where better to worship a solar god like the Aton? Similar temples probably existed at the ancient city of Heliopolis, today a trendy part of Cairo, but the normal Egyptian temple plan had a very different plan and symbolic layout. Ramses III's mortuary temple of Medinet Habu in the great necropolis of Thebes was dedicated to Amun-Re, the head of the Egyptian pantheon at that time, and reflects the ideal layout of an Egyptian temple better than any other surviving monument. By acting as a bridge between divine and mundane, Egyptian temples The archetypical Egyptian temple linked heaven, earth and the Netherworld through mystical and magical connections. The ideal temple plan moves from open to restricted and light to dark space. A bright courtyard is followed by the twilight of the hypostyle “Hall of Appearances,” which is in turn followed by a series of inner rooms of increasing darkness, with only a few openings in the ceilings and walls casting mysterious, isolated shafts of light, a hidden realm largely restricted to the priesthood and elite.

|

Roll your curser over different parts of the temple and click to see more!

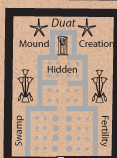

In keeping with the New Kingdom theological shift in royal burial practice, Medinet Habu is laid out along the lines of a temple for the living, and actually served as an important cult place for Amun-Re, the head of the Egyptian pantheon during the New Kingdom. Like his predecessors, the king’s tomb lay in the Valley of the Kings. The space before the entrance pylon and large porticoed courtyards that followed were accessible to the ordinary worshipper, explicitly indicated by inscriptions naming the Rekhit “masses” praising the god in these locations. The Rekhit are symbolized in hieroglyphs and iconographically in temple decoration by the lapwing, a plentiful, small and very noisy bird. The Rekhit still had access to a kind of twilight space in the large hypostyle hall with a clerestory running down the central aisle, supplemented by holes in the roof for subdued lighting. Darker still and more restricted of access were the offering chambers that lay before the shrine wherein the god resided, which only the king or a purified priest could approach. The exterior was decorated with scenes of battle and the subduing of foreign enemies, symbolizing the king’s triumph over the earthly powers of Isfet (evil, wrong) and by analogy Re’s battle with the evil snake god Apophis, who threatened to destroy all creation. The temple is surrounded by representations of Isfet, the scenes of battle symbolically and magically protecting the Ma’at, (order, right) which lies inside. In order to represent creation surrounded by chaos, the temple lies on a slope, gently ascending to the sanctuary, where the deity sits in his or her shrine upon an artificial rise symbolizing the mound of creation that arose from the primordial waters of Nun. Column capitals that mimic papyrus and lotus blossoms denote the fertile creative forces that surround the primordial mound, where all life began. The sanctuary itself represents the Duat, or Netherworld, a dark underground land visited by Re during the night. Like royal crypts going back to the Old Kingdom pyramids, the inner ceilings of temples were decorated with stars symbolizing the dark realm of the Duat. Scenes in this part of the temple stress festivals and the daily rituals and offerings given to the deities worshipped in the temple. Only the king and very rarely his chief queen are represented here among the gods and goddesses of Egypt, stressing the royal role as intermediary between humans and the divine. The temple rituals enact the daily journey of the sun, with the god or goddess emerging from the sanctuary-Duat toward the pylon-Akhet (horizon) at dawn and returning each night. Egyptian theologians named the entrance to the sanctuary the “Doors of Heaven.” The innermost shrine itself was called the Duat-en-Ba, a Netherworld for (the divine) Ba (soul). Each day the god arose in the morning rituals as a regenerated Ba emerging from the Duat.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||